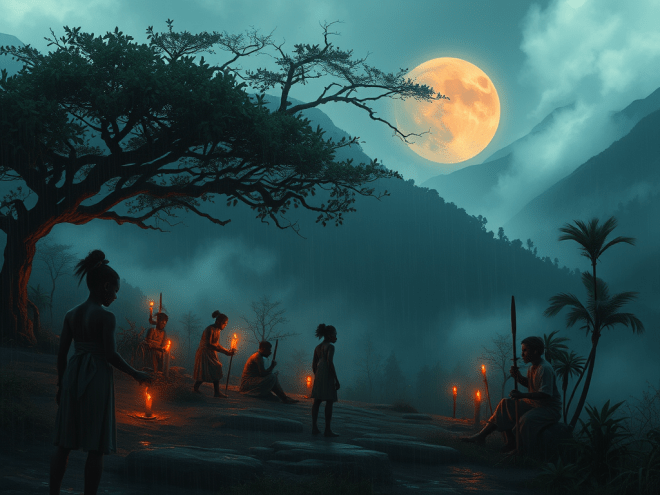

Weeks passed. Rain returned, flooding the streets until the city became a mirror. Noluntu walked through it barefoot, her reflection rippling like a ghost trying to break free. She’d begun writing again—long, fevered passages about justice, order, divine law.

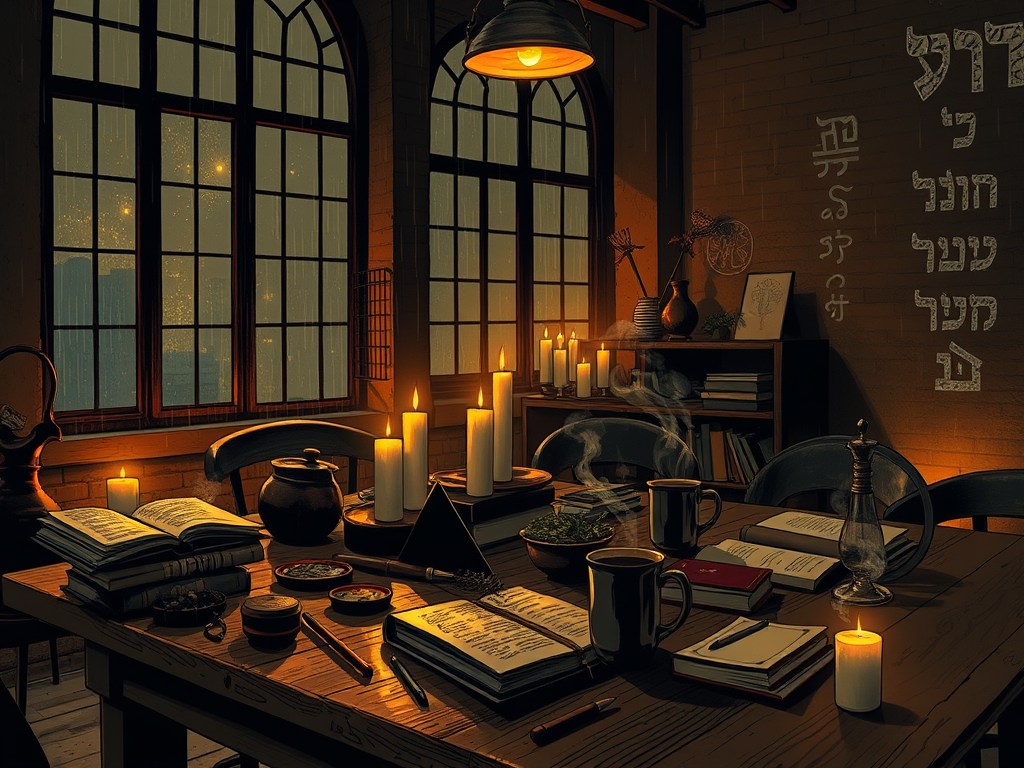

By now, she had gathered a small circle around her: musicians, writers, young activists disillusioned with politics but hungry for meaning. They met in her loft, where candlelight replaced screens. They called themselves The Rememberers.

They read Scripture, the works of Biko and Fanon, the poetry of Mazisi Kunene, and the proverbs of the desert. They debated democracy and divine kingship, love and liberation, witchcraft and worship.

In these gatherings, Noluntu’s leadership became natural, effortless. Her words carried a quiet authority that both soothed and unsettled. She taught that the true revolution was inward, that Africa’s first colonisation was spiritual.

“God gave us dominion,” she told them one night. “But dominion begins with mastery of self. What good is political freedom if our minds are still enslaved?”

They listened, entranced. Some whispered that she was a prophet. Others feared she was becoming something else entirely.

Asher reappeared, silent as ever. He watched her speak, his eyes full of an unspoken ache. When the others left, he lingered.

“You’re changing,” he said softly.

“So are you.”

He smiled. “You’ve remembered enough to be dangerous.”

She met his gaze. “Then teach me the rest.”

He hesitated. “There are things you can’t unsee. Powers that don’t serve the light you think they do.”

“Light can blind,” she said. “Darkness can reveal.”

For the first time, he looked almost afraid. “Then you’ve already begun the trial.”

Outside, thunder cracked like a drumbeat. Somewhere in the city, a statue of a colonial general collapsed under mysterious fire.